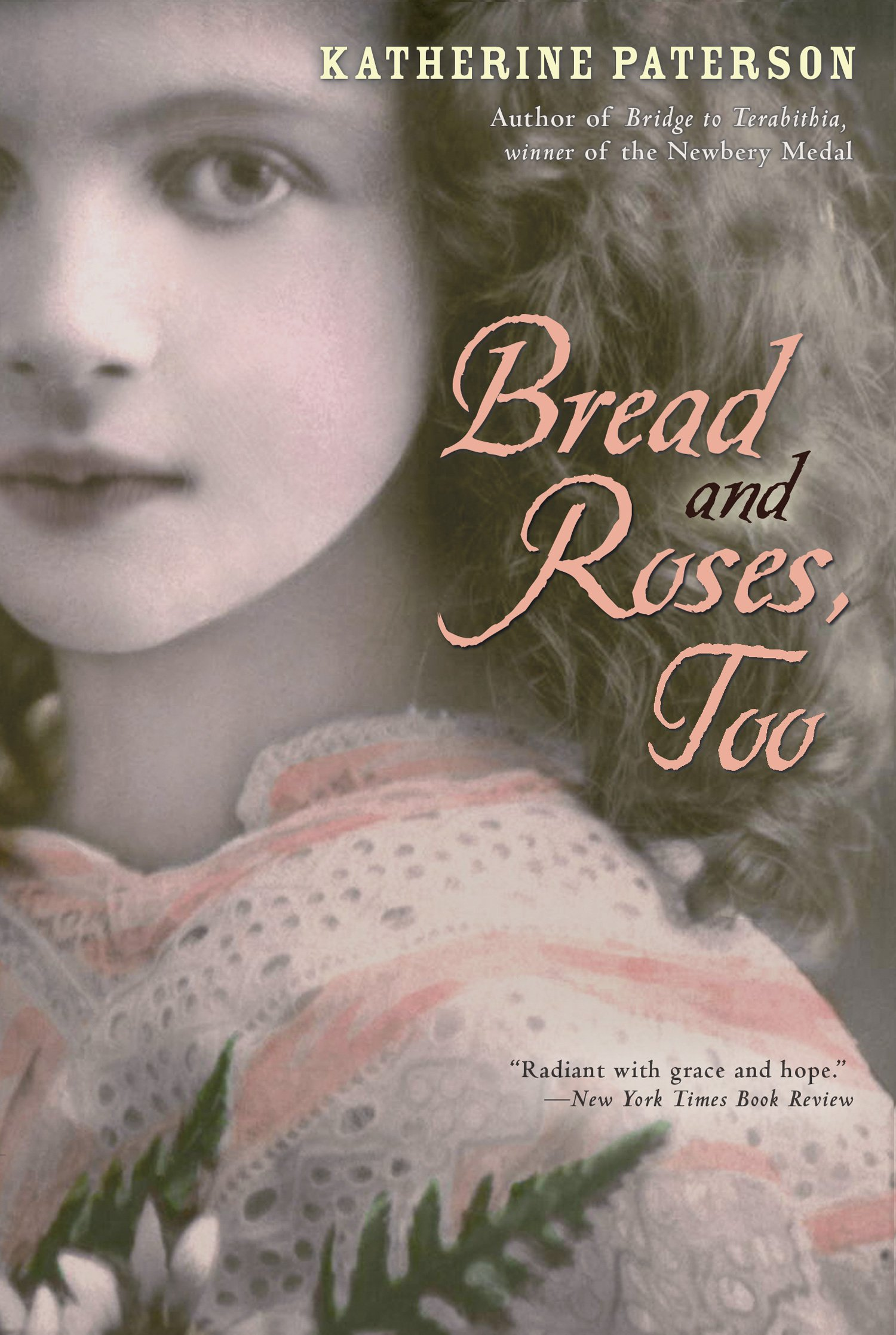

Review Unwritten—Katherine Paterson’s Bread and Roses, Too

Just after putting down this latest Paterson book, I had idea after idea about what to say. That was a month ago (at least) and the details have now faded. All my brilliant points of critique, all my Deep Thoughts. Oddly, details of the story itself are not lost, nor are one or two things I’d thought when I first read it. This is probably for the best—the things that remain will be the most important.

I’m reading a printed collection of Katherine Paterson’s lectures, The Invisible Child. The first is titled, “In Search of Wonder,” and in it she writes,

“If knowledge without a sense of reverence is dangerous, morality divorced from wonder leads either to chilling legalism or priggish sentimentality. I am always nervous when some well-meaning critic applauds my work for the values and lessons it teaches children, and I’m almost rude when someone asks me what moral I am trying to teach in a given book. When I write a book I am not setting out to teach virtue, I am trying to tell a story, I am trying to draw my reader into the mystery of human life in this world. I am trying to share my own sense of wonder that although I have not always been in this world and will not continue in it for too many more years, I am here now, sharing in the mystery of the universe, thinking, feeling, tasting, smelling, seeing, hearing, shouting, singing, speaking, laughing, crying, living, and dying.”

As she has in the past, Paterson accomplished this in Bread and Roses, Too.

Through careful research she effortlessly transports us back in time. Effortlessly, we hear the distinct accents of the Italian ladies, and the Polish ladies, and the Lithuanian ladies. Effortlessly, we fall into the lives of daughter of Italian-immigrants, Rosa and US-born, Jake. And as Paterson has done in many of her novels, she succeeds in her treatment of difficult subject matter.

Paterson is well aware of her tendency toward taking on challenging topics. From the essay, "Creativity Limited," reprinted in The Invisible Child, but dating back to The Writer in 1980, she writes,

“Let me offer a brief and brutal survey of my already published novels for children and young adults. In the first, the hero is a bastard, and the chief female character ends up in a brothel. In the second, the heroine has an illicit love affair, her mother dies in a plague, and most of her companions commit suicide. In the third, which is full of riots in the streets, the hero’s best friend is permanently maimed. In the fourth, the central child character dies in an accident. In the fifth, turning away from the mayhem in the first four, I wrote what I refer to as my “funny book.” In it the heroine merely fights, lies, steals, cusses, bullies an emotionally disturbed child, and acts out her racial bigotry in a particularly vicious manner.”

This is just her first five books. In Bread and Roses, Too, Paterson confronts head-on alcoholism, abuse, and again bigotry, without glossing over or authorial judgment.

Paterson writes her world as it exists for her characters. In the same lecture, she writes,

“Yet, somehow, when a story is coming to life, I’m not judging it as appropriate or inappropriate, I’m living through it. In The Sign of the Chrysanthemum Akiko ended up in a brothel not because I wanted to scandalize my readers, not because I’m advocating legal prostitution, but because in twelfth-century Japan, a beautiful thirteen-year-old-girl with no protector would have ended up in a brothel.”

Likewise, when Jake is cleaned up by a young priest after being beaten bloody by his drunken father, the priest shudders, but does not run out and call Child Protective, or vow to stop the monster who did this. No, he clothes Jake and sends him back out on the street. Other issues are dealt with similar deftness. Rosa’s devout Catholicism, the harsh effects of life in the mills are but two more examples.

Yet with all this praise, Bread and Roses, Too is not my favorite Paterson work. I have two reasons and both have to do with characterization. First, I found Rosa’s continual negativity tiresome and it kept me from fully identifying with her. At every turn she is wary of the events taking place in the book, fearful, and generally a wet blanket over the enthusiasm of her mother and sister. Having a character with these traits is fine in moderation – it gives her something to overcome – but I found Rosa's struggle more caused by obstinance (or the author's manipulation) than believable struggle. I rooted for her mother and sister, but spent more time wishing I could just shake Rosa by the shoulders, “Get with it, girl!” than looking forward to what might happen to her next.

Along the same lines, there is an unresolved tension between Rosa and Jake as to who takes center stage. The novel opens with Jake digging a hole for himself in the trash heap, and shortly the point of view switches to Rosa. I love books with multiple points of view – the scope it gives, broadening out from one character’s often myopic view of the world. But, often one character is considered the protagonist or lead.

Because more weight, in terms of page numbers and emotional intensity (all that angst and negative energy), is given to Rosa, I assumed she was the lead and big changes would be in store. Yet toward the end of the book I realized that was not the case – Rosa doesn’t change in any life-shattering way. She accepts and gets behind the central movement of the plot eventually, but I was never fully convinced of her ambivalence in the first place (as said, it seemed more a convenience for the sake of plotting), so this wasn’t so big of a surprise. The real change comes in Jake, who goes from being a selfish little trash-digging rogue, to an upstanding young man, with a loving family, no less. This made Rosa seem more a vehicle than a real person. A vehicle to drive the plot, but also one to drive theme, and this I noted particularly in her line toward the end regarding all her prayers being answered but one, that one being for Jake, which by the end is also answered. This treatment is far less deft and subtle than I’m used to with Paterson, and was a disappointment.

That said, Bread and Roses, Too still brought out the tears and still made for a fulfilling read. The history is vibrant, the dialects superb, the characters lively, and the plot satisfying despite those minor qualifications.

The End of the Wild is a sweet little story about fracking. No, not really. It’s about a little girl named Fern coming to term with her mother’s death. Well not really. It’s about what it takes to win the science fair (otherwise known as STEM fair). Except really it’s about a poor girl in a small Michigan town who has to decide between her rich grandpa and poor stepdad. Or maybe it’s about nature, preserving the woods or friendship, or dogs...